At the end of the 19th century, French society was torn apart by the obscure events around the treason conviction of army Captain Alfred Dreyfus. The question of his guilt was probably the most debated issue in France for nearly 10 years. This discussion not only took place in private conversations, but had also an enormous presence in the press. It is a great example of the newly gained freedom of the press and shows how harsh the competition in the newspaper business must have been already back then. There were several leading newspapers in France, and with only little ad space it was up to the scandalous headlines to accomplish the necessary run. With Europeana Newspapers you can discover the whole variety of the coeval press.

On 15 October 1894 nobody could have presaged that this affaire would go down in history as a symbol of injustice, intrigues and anti-Semitism. Today, 121 years ago, Dreyfus (who had a Jewish background) was arrested for treason in all secrecy. He was accused of communicating French military secrets to the German Embassy and brought to imprisonment on Devil’s Island with a life sentence. As the main piece of evidence was a handwritten letter, the whole country turned into graphologists as Le Martin and Le Figaro published a facsimile of this letter. After five years of custody, the case of Alfred Dreyfus was brought to court-martial again in June 1899 (cf. the catholic-conservative newspaper La Croix). At this time, there could have been no more doubt about Dreyfus’ innocence. Nevertheless, he was sentenced again, this time to ten years in prison under extenuating circumstances. Shortly thereafter, he was pardoned by the President of the Republic, but only after six years he reached the annulment of the judgment of Rennes. The real culprit, Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, was acquitted and innocent Dreyfus was charged guilty twice. The affair did not only cause sensation in France, but was monitored critically all over Europe, for example in the Finnish Uusi Aura, the Dutch Algemeen Handelsblad, or the German Volkszeitung and Neue Hamburger Zeitung.

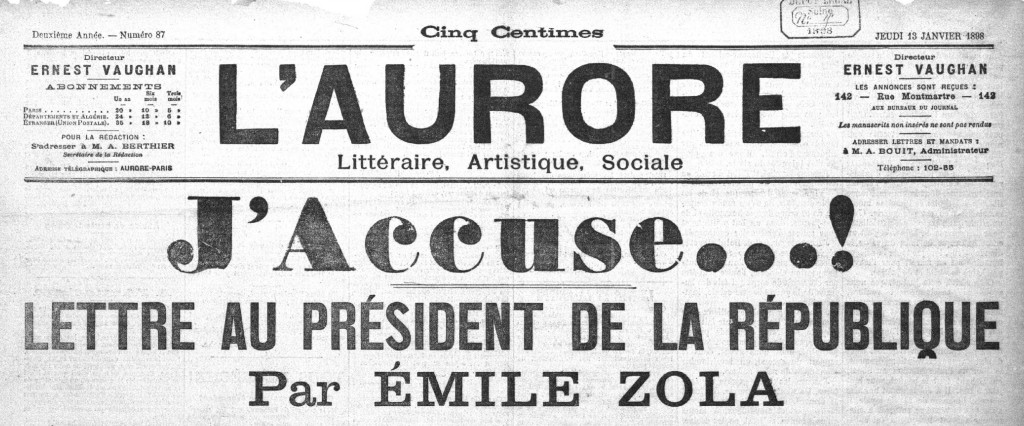

A lot of French intellectuals were convinced of Dreyfus’ innocence; most prominent amongst them the journalist and novelist Émile Zola. While Zola refused to get involved into political affairs at first, the increasing anti-Semitism in the public debate changed his mind. He published several articles in Le Figaro, amongst others one with the headline Le Syndicat, where he picks up on the imputation a Jewish syndicate tries to buy Dreyfus out of prison, or the article Procès-verbal, expressing his hope that the nation would reconcile and overcome the barbaric anti-Semitic resentments. Shortly after this, Le Figaro terminated the cooperation with Zola because anti-Dreyfusards and right-wing nationalists threatened to call out a boycott on the newspaper. Therefore, Zola published his next article in the newly founded literary journal L’Aurore. J’accuse was an open letter to the president of the French republic, Félix Faure, which caused an enormous scandal and was the decisive factor for the turnaround in the Dreyfus-Affair. Even today, the term “J’accuse” is a synonym for a brave public expression of opinion against the abuse of power. Émile Zola was hereupon sued for libel, as he had already expected at the end of his famous letter.

Despite such famous public advocacy, it was not until July 1906 that Alfred Dreyfus was acquitted and fully rehabilitated in the French society and also in the military service. A general pardon was enacted, that also included the accusation against Émile Zola (see debate in L’Intransigeant).

In the twelve years lasting Dreyfus-Affaire, France was confronted with intrigues, fraud, resignation and overthrow of ministers and the parliament, riots, assassinations, suicides, the attempt of a coup d’état and an alarmingly widespread anti-Semitism. The power of the media grew over the affair in a startling way. Without the contemporary coverage in the newspapers, the Dreyfus case would probably not have become a national affair, nor had intellectuals like Zola publicly taken a position. Therefore, the affair is considered by many to be the birth of the “intellectuals”, a term that was coined during that period through national, right-wing and clerical circles and used derogatory for those journalists, writers, artists and left-wing politicians who fought for Dreyfus. Out of this circle of intellectuals emerged the French Human Rights League in 1898, who in 1922 initiated the first international umbrella organisation of the human rights movement.

The rehabilitation of Dreyfus’ was an example of the long, but in the end successful fight by a democratic and humanitarian-socialist ideals group of intellectuals. The consequences of the affair were a milestone in Europe’s collective memory and sharpened the social and political consciousness.

wow this article is amazing i like that