Within the Europeana Newspapers project, we often speak of the value of historic newspapers for the academic community but how exactly might a researcher use the material that we’re gathering?

To answer that question, we’re interviewing scholars about their work with historic newspapers. Our most recent conversation was with Bob Nicholson, a historian of 19th-century popular culture at Edge Hill University.

He used newspaper archives extensively to research his PhD thesis, which included an examination of how content — and in particular jokes and slang — moved between America and Britain in the 1800s.

How did you discover the link between your research topic and newspapers?

It was quite accidental and goes back to before we had access to digital newspapers. I was in a local library helping my dad to do research. He’s also a historian. I was only about 17 years old and we were looking through microfilms related to his research when, completely by accident, I came across a column of imported American jokes. I never expected to see that in a newspaper from the 1880s. I thought: “This is unusual. Where have these come from?”

Over the next few years, bit by bit, I started to map these connections and what I discovered is that there is an enormous amount of content from America in British newspapers and vice versa. It was an accidental discovery but what digital archives allowed me to do was to really turn that accidental discovery into something much bigger. I wrote an essay about it for my MA. That turned into my PhD and I’m now turning that into a book.

You clearly found plenty of material to work with!

Yes, and this is perhaps the problem with digital archives more generally. There is just so much stuff. Every time I find a connection it leads me on to a new research topic. In the end I have enormous amounts of research and I never get anything finished because I always find something new. It’s a nice problem to have in the sense that I’m never going to run out of ideas but it also means that turning it into a book or a cohesive piece of research is tricky.

I remember that one of the first things I did at the start of my PhD research was to put the word America into one of the digital newspaper databases. It inevitably came back with millions and millions of hits and I could just see the next 10-20 years of my life standing there before me and thinking “I’m never going to get through all of these”.

How has this work affected your view of newspapers?

There were two things that changed for me. The first was my own approach to newspapers. When I started my own idea was to do what a lot of historians do, to mine them for information. I wasn’t really interested in the work that newspapers perform themselves. I just thought “wow, this is an enormous bank of 19th century culture that I can look through to find what the Victorians thought about America”. After a few months, I realised the agency of newspapers and the power they had to shape this process. I realised just how powerful newspapers were and the influence they had on 19th century culture.

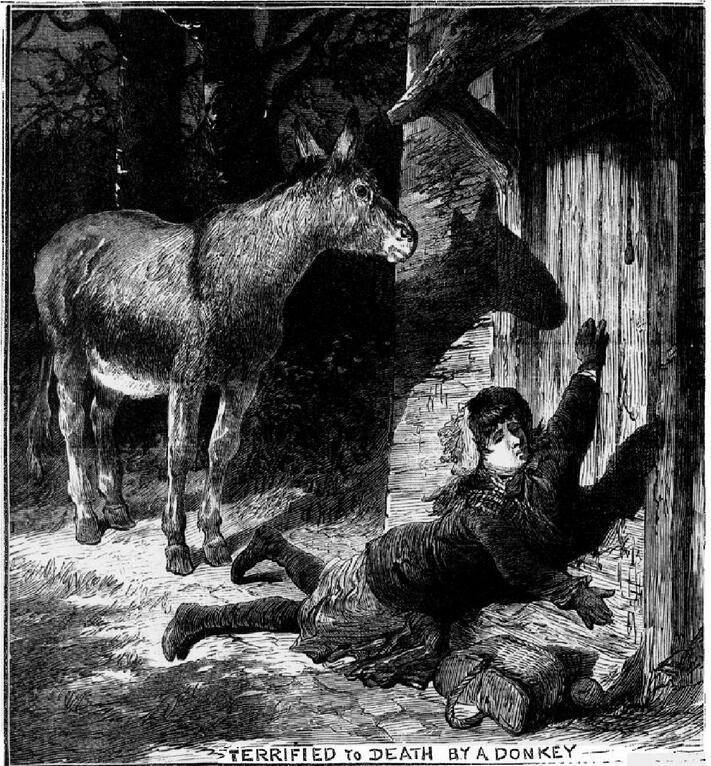

The content also surprised me. Almost every time I go into a newspaper I find something unexpected and that’s one of the great pleasures of using them. They contain an extraordinary amount of unusual things. All of the world is in there. Every aspect of 19th century culture, just about, is captured in some form either accidently or deliberately. It means that they are an almost endlessly useful resource. As a cultural historian, I think I’ll be using them for the rest of my life.

How would you compare them to other sources of information such as books and journals? Are there certain aspects of newspapers that just can’t be replicated anywhere else?

Newspapers don’t exist in a sealed off world. They’re on a shelf right next to a magazine or a book and people walk past talking about them so I wouldn’t look at newspapers just on their own but I do think they give us something quite distinctive.

One of the things is the fact that they are appearing every day or every week. As historians we’re interested in change and there is nothing that is more useful than being able to take a text and see how, on a daily or weekly basis, things change within it. A book is a single text in a moment in time whereas newspapers allow you to track change in a number of ways.

The phrase that newspaper historian Martin Conboy uses for newspapers is that they have a heteroglossia, a number of voices. I love that, the fact that they’ve been written by a number of people in a number of styles. This makes them quite unique.

I’d like to go on to how you actually do your work. You primarily use digital archives. Is that correct?

It is, yes. My entire research is dependent on them now. I rarely use paper or microfilm copies unless I really have to. Since I started my MA around the same time as the British Newspaper Archive was launched, I could design my doctorate research entirely around the use of digital archives, with a view to exploring the methodological possibilities. Of course I did look at some paper copies (there are some absolutely vital newspapers that I could only get on microfilm) but for the most part I’ve designed everything I’ve done since 2007 around digital archives.

What is your work process? Do you perform simple searches or do you download material and mine it for information?

Most British newspapers are behind paywalls, which means that as researchers we don’t have the ability to download material and mine it. I’ve had to use the existing interfaces. Thankfully I was able to do reasonably good keyword searching within the archives.

Most British newspapers are behind paywalls, which means that as researchers we don’t have the ability to download material and mine it. I’ve had to use the existing interfaces. Thankfully I was able to do reasonably good keyword searching within the archives.

I also developed a very basic sort of text mining myself where I did searches and tracked the frequency of certain terms appearing within the newspapers. It was very laborious. In the end it took me a day to perform each search. It would have taken me about 30 seconds using a proper tool but I did find some very useful material for illustrating big changes relative to my PhD. This work was critical because, as I said before, if you have a million newspapers mentioning the term “America” there’s no way you can read them all so I needed a way to “distant read” them and uncover the patterns. I would love to have better tools to do that automatically.

Do you ever worry that you may have missed material because you were limited to what had been pre-selected to appear in digital archives?

There were some papers that I knew I wanted to look at which weren’t digitised so I did what we all used to do and spent a week in the archives looking at material. I bought things online if I had to. But the fact is that I could access somewhere in the region of 1,000 titles from the 19th century from home. There’s no way that even five years earlier I would have been able to look at 5% of those things for my PhD so I wasn’t too anxious. I knew that the benefits of digital archives massively outweighed the problems.

If you look forward 10 years, what would you like to see?

What I would really love is to liberate newspapers from behind the paywalls so that we could start doing more interesting things with them. The best research projects that I’ve encountered in the digital humanities are completely open and allow us to do incredible things. I’d like to be able to do more proper text mining, tracking the frequency of words automatically. That’s at the top of my list currently. For me, we have enough content. It’s more about developing the tools to make the most of it.

I’d also like to ask about extending your work across borders. The digital archive that we’re building is pan-European. What potential do you see for that body of material?

The work I’m doing is very trans-national so I’ve had to make links between different databases in ways that are sometimes quite tricky. I see enormous value in an archive that breaks down national boundaries automatically, where I can search for content from a range of countries. There’s huge potential to look at newspapers on a pan-European perspective.

The problem for me and I imagine a lot of British and American scholars will be the language barrier. My language skills are terrible and I don’t know whether I’ll actually be able to make the best use of those resources but I can see enormous potential. If we don’t have to learn to read the languages at a native level, we might still be able to search for certain words and then through translation software we might still be able to find those connections.

Maybe you could also collaborate with researchers in other countries and overcome the language barrier in that way.

That’s obviously what digital archives allow us to do. They break down systems where earlier you’d have to sit, for example, in a specific room in London to do research. That change should, at least in theory, allow us to have these sorts of collaborations. One of the weird things about historians is that we don’t seem to work in those collaborative lab-based environments as much as in other disciplines but if I could find somebody who’d be willing to spend their life looking at 19th century jokes in German that would be great.

Before we close this interview, I just have to ask. What’s the best joke you’ve found during your research?

I always get this question! The problem is that when you’ve read about 10,000 jokes you lose any kind of ability to decide what is funny anymore. It warps your sense of humour. Also, jokes in newspapers aren’t really designed to be told orally. I do have one joke that I’ve told at tons of conferences and almost invariably no one laughs at it. It creates this incredibly awkward silent moment but I can share it with you.

CHICAGO WOMAN: What do you charge for securing a divorce?

CHICAGO LAWYER: $100 ma’am, or six for $500!

Bob Nicholson can be found online via his website The Digital Victorianist. You can also follow him on Twitter: @DigiVictorian.